Updates for publishing

This commit is contained in:

7

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/_index.md

Normal file

7

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/_index.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

title: March 2020

|

||||

# type: blog

|

||||

description: All posts in March 2020

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

{{< listofposts "2020-03" >}}

|

||||

321

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/metapython.md

Normal file

321

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/metapython.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,321 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

layout: post

|

||||

title: "python: metaprogramming marshmallow"

|

||||

author: mjadud

|

||||

tags:

|

||||

- cc-sa

|

||||

- python

|

||||

- metaprogramming

|

||||

- blog

|

||||

- "2020"

|

||||

- 2020-03

|

||||

publishDate: 2020-03-19

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

## tl;dr

|

||||

|

||||

I used Python's metaprogramming features to auto-generate Marshmallow schemas that correspond to `attrs`-derived data classes.

|

||||

|

||||

If you like the thought of thinking about metaprogramming as much as I do, you'll grove on this post.

|

||||

|

||||

## a theme of metaprogramming...

|

||||

|

||||

*Oddly, related as a piece to my explorations of `tbl` in Python, as well looking at GraphQL, but still it's own post...*

|

||||

|

||||

It is hard to extend Python's syntax, but that doesn't mean you can't engage in some dynamic metaprogramming in the language. While it isn't always the first tool you should reach for, it can be nice for **reducing boilerplate**.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, I am staring down a bunch of JSON-y things. They come-and-go from the front-end to the back-end:

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

{ email: "vaderd@empire.com",

|

||||

token: "89425abc-69f9-11ea-b973-a244a7b51496" }

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Let's pretend that the front-end is [React](https://reactjs.org/), the storage layer is [MongoDB](https://www.mongodb.com/), and the middleware is [Flask](https://palletsprojects.com/p/flask/) (a Python web framework).

|

||||

|

||||

<img src="{{ site.base }}/images/posts/react-flask-mongo.png"

|

||||

alt="react<->flask<->mongo"

|

||||

>

|

||||

|

||||

At the Flask layer, there's a lot of work that needs to be done: the JSON comes in, and in the first instance, it comes in as a dictionary. This is not very nice. By "not very nice," I mean "dictionary convey no notion of types or the regularity of their contents, and therefore provide us with no notion of safety." What I'd like is for the data coming from the front-end to be strongly typed and well described, the middleware to be aware of those types, and the database to help enforce them as well. (I'm thinking GraphQL starts to do things like this... almost.)

|

||||

|

||||

BUT, we have a RESTful web application sharing data in webby, untyped ways. This inspired me to do some digging. First, I found Flask Resful, which is a nice library. It lets you define a class, set up `get`, `put`, `post`, and other methods on endpoints, and register them with the app. Leaving a bunch of bits out, this looks like:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

from flask_restful import Resource, Api

|

||||

import db.models as M

|

||||

import db.db as DB

|

||||

|

||||

class Tokens(Resource):

|

||||

def post(self, email):

|

||||

# Create a UUID string

|

||||

tok = str(uuid.uuid1())

|

||||

# Create a TimedToken object, with a current timestamp

|

||||

t = M.TimedToken(email=email, token=tok, created_at=time())

|

||||

# Grab the correct collection in Mongo for tokens

|

||||

collection = DB.get_collection(M.TimedToken.collection)

|

||||

# Save the token into Mongo by dumping the token through marshmallow

|

||||

as_json = t.dump()

|

||||

collection.insert(as_json)

|

||||

# Return the token as JSON to the client

|

||||

return as_json

|

||||

|

||||

mapping = [

|

||||

[Tokens, "/token/<string:email>"]

|

||||

]

|

||||

|

||||

def add_api(api):

|

||||

for m in mapping:

|

||||

api.add_resource(m[0], m[1])

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

which is in a module called "API", and at the top level of the app:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

from flask_restful import Api

|

||||

from flask import Flask

|

||||

import hydra

|

||||

from api.api import add_api

|

||||

|

||||

app = Flask(__name__)

|

||||

|

||||

@hydra.main(config_path="config.yaml")

|

||||

def init(cfg):

|

||||

# Dynamically define classes from the YAML config.

|

||||

M.create_classes(cfg)

|

||||

# Set the Mongo params from the config.

|

||||

DB.set_params(cfg.db.host, cfg.db.port, cfg.db.database)

|

||||

# Add the REST API to the app.

|

||||

A = Api(app)

|

||||

add_api(A)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This is a lot to take in, but I'm actually trying to get to the good bit. The top level has an `init` function that reads in a configuration file (more on that later), and uses that to build a whole bunch of classes *dynamically at run time*. (This is the cool bit.) Those are instantiated in the `models` submodule of `db`, and they get used throughout the application.

|

||||

|

||||

Looking back at the first code block, it's possible to see some of those uses. For example, I'm creating a timed token (e.g. a random string associated with a user that will ultimately have a finite lifetime).

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

t = M.TimedToken(email=email, token=tok, created_at=time())

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This class takes three parameters: `email`, `token`, and `created_at`. The whole purpose of the class is that I want it to serve as a `struct` (in Racket or C) or `record` (in... Pascal?). In Python, `namedtuple`s, `dataclass`es, and classes decorated with `attrs` are all examples of what I'm aiming for.

|

||||

|

||||

But... **BUT**... I also want easy marshalling to-and-from JSON. The front-end speaks it, and Mongo speaks it... but, while I'm in the middle, I need to interact with it. I would like it to be *typed* (in as much as Python is typed) while I am working with it in the middleware. And, I'd rather not do the conversions myself. (Why would I write code if I wanted to do all the hard stuff by hand?)

|

||||

|

||||

To solve this, enter [marshmallow](https://marshmallow.readthedocs.io/en/stable/). This Python library lets you define schemas for classes, and in doing so, leverage machinery to marshal JSON structures to-and-from those classes. For example, my `TimedToken` class looks looks (er, used to look like):

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

@attr.s

|

||||

class TimedToken:

|

||||

email = attr.ib(type=int)

|

||||

token = attr.ib(type=str)

|

||||

created_at = attr.ib(type=float)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

To marshal this to-and-from JSON, I can use marshmallow. I need to create a schema first:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

from marshmallow import Schema, fields

|

||||

|

||||

class TimedTokenSchema(Schema):

|

||||

email = fields.Str()

|

||||

token = fields.Str()

|

||||

created_at = fields.Number()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Once I have a schema, I can do things like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

a_token = TimedToken(...)

|

||||

schema = TimedTokenSchema()

|

||||

as_json = schema.dump(a_token)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The machinery inside of marshmallow will take an object of type `TimedToken`, a schema describing them (`TimedTokenSchema`), and use the schema to walk through a `TimedToken` object to convert it to JSON (and, back, if you want).

|

||||

|

||||

This is cool.

|

||||

|

||||

But, it's not automatic. And, for every data structure I want to create in my app, I need to write a schema. This is duplicating code. If I change a structure, I need to remember to change the corresponding schema. *That isn't going to happen*. What's actually going to happen is that I'll forget something, and everything will break.

|

||||

|

||||

## enter metaprogramming!

|

||||

|

||||

I wanted to be able to declare my data structures as YAML, and then have Python generate both the `attrs`-based class as well as the `marshmallow`-based schema. Is that so much to ask? No, I don't think it is.

|

||||

|

||||

Using Facebook's [Hydra](https://hydra.cc/), I created a config file. This important bit (for this discussion) looks like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```yaml

|

||||

models:

|

||||

- name: TimedToken

|

||||

fields:

|

||||

- email

|

||||

- token

|

||||

- created_at

|

||||

types:

|

||||

- String

|

||||

- UUID

|

||||

- Number

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Then, the fun bit is the function `create_classes`. It takes a config that includes the `models` key, and does the following:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

def create_classes(cfg):

|

||||

for c in cfg.models:

|

||||

make_classes(c.name, c.fields, c.types)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

OK... so, `make_classes` must do the interesting work.

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

def make_classes(name, fs, ts):

|

||||

# Dynamically generate the marshmallow schema

|

||||

schema = make_schema(fs, ts)

|

||||

# Generate a base class, and wrap it with the attr.s decorator.

|

||||

base = attr.s(make_base(name, fs,ts, schema))

|

||||

# Insert the class into the namespace.

|

||||

globals()[name] = base

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This is probably **really bad**. But, it's fun, so I'll keep going.

|

||||

|

||||

I pass in the name of the class as a string (`"TimedToken"`), and then I pass in the fields as a list of strings, and their types as a list of strings. (These are given in the YAML, above). The last line here is where the evil happens. The function `globals()` returns the dictionary representing the current namespace. I proceed to overwrite the namespace; specifically, I insert a new class of the name `TimedToken` (in this example). (I *hope* the use of `global()` is restricted to the *module*, and not the entire *application*... I have some more reading/experimenting to do in that regard. It *seems* like it is the module...)

|

||||

|

||||

Backing up, I'll start with `make_schema()`. It takes the fields and types, and does the following:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

def make_schema(fs, ts):

|

||||

# Create an empty dictionary

|

||||

d = {}

|

||||

# Walk the fields and types together (using zip)

|

||||

for f, t in zip(fs, ts):

|

||||

# Convert each type into the appropriate fields.X from marshmallow

|

||||

# and insert it into the dictionary

|

||||

d[f] = get_field_type(t)

|

||||

# Use marshmallow's functionality to create a schema from a dictionary

|

||||

return Schema.from_dict(d)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

`get_field_type()` is pretty simple:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

def get_field_type(t):

|

||||

if t == "Integer":

|

||||

return fields.Integer()

|

||||

if t == "Float":

|

||||

return fields.Float()

|

||||

if t == "String":

|

||||

return fields.String()

|

||||

if t == "UUID":

|

||||

return fields.UUID()

|

||||

if t == "Number":

|

||||

return fields.Number()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

(No, there's no error handling yet. Not even a default case... *sigh*.)

|

||||

|

||||

The `make_schema` function literally returns a `class` that I can use to convert objects that match the layout of the dictionary that I built. That's great... but what good is a `TimedTokenSchema` if I don't have a `TimedToken` class in the first place? Hm...

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

|

||||

@attr.s

|

||||

class Base ():

|

||||

pass

|

||||

|

||||

def make_base(name, fs, ts, schema):

|

||||

cls = type(name, tuple([Base]), {})

|

||||

setattr(cls, "schema", schema)

|

||||

setattr(cls, "dump", lambda self: self.schema().dump(self))

|

||||

setattr(cls, "collection", "{}s".format(name.lower()))

|

||||

for f, t in zip(fs, ts):

|

||||

setattr(cls, f, attr.ib())

|

||||

return cls

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The function `make_base()` does some heavy lifting for me. First, it uses the `type()` function in Python to dynamically generate a class. In this case, it will create a class with the name `TimedToken`, it will use `Base` as a superclass, and it will attach no attributes at time of creation. (I actually do not want to overwrite anything, because `attrs` does a lot of invisible work.)

|

||||

|

||||

The function `setattr` is, used casually, probably a bad thing. It literally reaches into a class (not an *object*, but a *class*) and attaches attributes to the class. If you're not used to metaprogramming, this is like... writing the code for the class on-the-fly.

|

||||

|

||||

I attach three attributes:

|

||||

|

||||

* `schema` is a field that will hold a marshmallow `Schema` class. (Because, in Python, classes are objects too! Wait...) If you look back, you can see that I pass it in after creating it in `make_classes()`.

|

||||

* `dump`, which is a function of zero arguments. It takes a reference to `self` (because this class will get instantiated as an object), and it instantiates the `schema` that I've stored, and then invokes `dump()` on... itself. This feels metacircular, but fortunately marshmallow knows to only look for fields that are in the schema. Therefore, we don't get an infinite traversal here.

|

||||

* `collection`, which is so I can map directly into Mongo. I take the name of the class, lowercase it, and add an 's'. So, `TimedToken` becomes `timedtokens` as a collection name. I like the idea of the object knowing where it should be stored, so I don't have to think about it.

|

||||

|

||||

Once I have these things set up, I walk the fields, and add them to the class. For each, I add a (currently) untyped `attr.ib()` to the field. This way, the `TimedToken` class will act like a proper `attrs` class.

|

||||

|

||||

Finally, I return this class, which then gets attached (back in `make_classes()`) to the `global()` namespace.

|

||||

|

||||

## what?

|

||||

|

||||

If you like the thought of thinking about metaprogramming as much as I do, you're excited at this point. If you're wondering why I would do this... well, I'll go back to my REST handler for TimedTokens:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

from flask_restful import Resource, Api

|

||||

import db.models as M

|

||||

import db.db as DB

|

||||

|

||||

class Tokens(Resource):

|

||||

def post(self, email):

|

||||

# Create a UUID string

|

||||

tok = str(uuid.uuid1())

|

||||

# Create a TimedToken object, with a current timestamp

|

||||

t = M.TimedToken(email=email, token=tok, created_at=time())

|

||||

# Grab the correct collection in Mongo for tokens

|

||||

collection = DB.get_collection(M.TimedToken.collection)

|

||||

# Save the token into Mongo by dumping the token through marshmallow

|

||||

as_json = t.dump()

|

||||

collection.insert(as_json)

|

||||

# Return the token as JSON to the client

|

||||

return as_json

|

||||

|

||||

mapping = [

|

||||

[Tokens, "/token/<string:email>"]

|

||||

]

|

||||

|

||||

def add_api(api):

|

||||

for m in mapping:

|

||||

api.add_resource(m[0], m[1])

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The function `create_classes(cfg)` is in the `db.models` module. I import that as `M`. Because I created classes in this module at the point that Flask was initialized, I now have a whole bunch of dynamically generated classes floating around in there. Those classes were generated *from a YAML file*, and can be used anywhere in the application.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

```yaml

|

||||

models:

|

||||

- name: TimedToken

|

||||

fields:

|

||||

- email

|

||||

- token

|

||||

- created_at

|

||||

types:

|

||||

- String

|

||||

- UUID

|

||||

- Number

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

To add a new class to my application, I add it to the YAML file, and restart Flask. This will call `create_classes` as part of the init, and the new class will be generated in the `db.models` module. I can then use those classes just as if I had written them out, by hand, duplicating the effort of defining both the `attrs` class and the marshmallow `Schema` class.

|

||||

|

||||

In my REST handler, this is where this dynamic programming comes into play:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

# Create a TimedToken object, with a current timestamp

|

||||

t = M.TimedToken(email=email, token=tok, created_at=time())

|

||||

# Grab the correct collection in Mongo for tokens

|

||||

collection = DB.get_collection(M.TimedToken.collection)

|

||||

# Save the token into Mongo by dumping the token through marshmallow

|

||||

as_json = t.dump()

|

||||

collection.insert(as_json)

|

||||

# Return the token as JSON to the client

|

||||

return as_json

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

I create the object. Then, I use the `collection` attribute to ask for a database connection to the collection that holds objects of this type (this is like a table in relational databases). Next, I convert the object to JSON by invoking the `.dump()` method, which was added dynamically. In fact, it is using a Schema class that was created dynamically as well, and then embedded in the enclosing object for later use. Finally, I insert this JSON into the Mongo database, and return it to the client, because both Mongo and the client speak JSON natively.

|

||||

|

||||

The result is that I've metaprogrammed my way around `attrs` and `marshmallow` to create a dynamic middleware layer that can marshal to-and-from JSON. In doing this, I've saved myself a large amount of boilerplate, and I have a single point of control/failure for all of my class definitions, which is external to the code itself. (I think I still need to add the marshalling *from* JSON, but that won't be hard.)

|

||||

|

||||

## what will you do with this, matt?

|

||||

|

||||

Personally, I haven't found anything on the net that eliminates the boilerplate in marshmallow. In the world of open source, I'd say this is an "itch" that I scratched. It might be an itch other people have.

|

||||

|

||||

Perhaps my next post will be about packing code for `pip`?

|

||||

29

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/so-much-fluff.md

Normal file

29

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/so-much-fluff.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,29 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

layout: post

|

||||

title: "python: marshmallow fluff..."

|

||||

author: mjadud

|

||||

tags:

|

||||

- cc-sa

|

||||

- python

|

||||

- metaprogramming

|

||||

- blog

|

||||

- "2020"

|

||||

- 2020-03

|

||||

publishDate: 2020-03-20

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

So, I still like my metaprogramming tricks. It was fun. I learned things.

|

||||

|

||||

But, I went to [PyPi](https://pypi.org/), and discovered they have a very nice search feature. [I searched for marshmallow](https://pypi.org/search/?q=marshmallow). I found... 263 projects referencing marshmallow. It's a unique enough word that I'm going to *guess* that they all interact with the `marshmallow` library in some way.

|

||||

|

||||

A lot of them do what I was exploring. For example, [marshmallow-objects](https://github.com/sv-tools/marshmallow-objects) does *exactly* what I was doing, but better.

|

||||

|

||||

(Well, mostly. Kinda.)

|

||||

|

||||

Actually, it is different. You still have to define Python classes... but, you can subclass a marshmallow model that gives you serialization/deserialization without having to write a separate schema. It wouldn't let me dynamically generate the classes from a YAML file (that's a neat trick, I think), but it might be fine to write the class as code. I mean, it's easier to test the class, whereas the dynamic trickery is just that...

|

||||

|

||||

So. Lesson learned. Or, if you prefer, a lesson I've always known, and taught my students many times: *do a search first*. Someone else has probably done it.

|

||||

|

||||

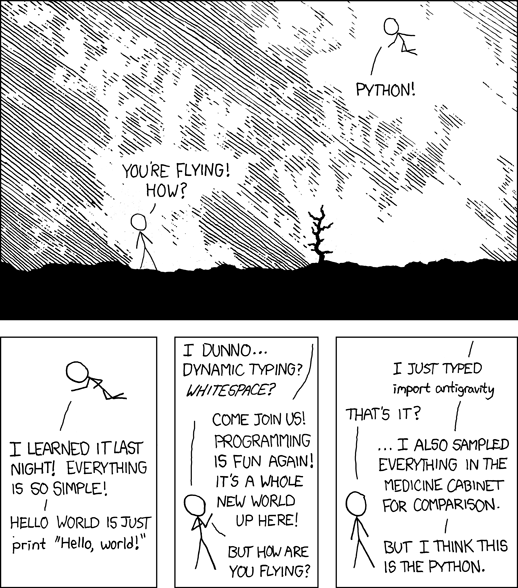

As the old joke goes:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

88

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/tbl-import.md

Normal file

88

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/tbl-import.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,88 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

layout: post

|

||||

title: "tbl: abstractions and imports"

|

||||

author: mjadud

|

||||

commit: https://github.com/jadudm/pytbl/tree/527b16bdecbf73b874103922cf3038a1f2c1e1c7

|

||||

tags:

|

||||

- cc-sa

|

||||

- tbl

|

||||

- blog

|

||||

- "2020"

|

||||

- 2020-03

|

||||

date: 2020-03-08

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

There is a debate in the data science community (and, in particular, in the R community) as to whether one should learn libraries or a core language when working with data. For R programmers, it is a question of learning the dyplr-family of libraries vs. working directly in the language without those tools. This is, from what I can gather, a sometimes divisive argument.

|

||||

|

||||

As an educator and a developer, I've come to appreciate the power of a good abstraction and tools that support that abstraction. I want tools that help me map the way I think about a problem directly into code. Or, I want tools that will shape the way I think about problems, so that I can more concisely express solutions using those tools. Here, "tools" means "libraries" or "programming languages."

|

||||

|

||||

My approach to working on `tbl` has therefore been to think about how to make it easy for beginners to work with interesting data. "Interesting" might mean it is personally meaningful, and possibly a small amount of data. "Interesting" might mean it is large and complex data... but, important to the developer. This means `tbl` needs to support data that is both small and big, and it needs to be easy for a developer to get started.

|

||||

|

||||

## Imports: The `tbl`

|

||||

|

||||

I want my beginner to be thinking about tabular data. So, I want a `tbl` to make it easy to turn a spreadsheet into something that they can do meaningful work with. In this way, the first abstraction that a programmer sees with `tbl` is the spreadsheet, and they can map that abstraction directly into the library. A `tbl` is, in the first instance, a spreadsheet.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

<img src="/images/posts/20200308-blue-lobster.jpg" align="right" width="20%" alt="Blue lobster photo by David Clode on Unsplash.">

|

||||

Here, for example, is the [spreadsheet](https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1aCjhAepc2Ms-eIr97hPb2FvzEKmqWK1w6mH8MnVUtRs/edit?usp=sharing) I use to keep track of my pet lobsters.

|

||||

|

||||

<div style='width: 100%;'>

|

||||

<iframe src="https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vSK2rd47ogfI2CpQi2L6HDo9AOEhnhqBN4zR4kLPUO28vBzmlc8XQWrvTfBYCU0ePf478yxcNKdOy5m/pubhtml/sheet?headers=false&gid=0&range=A1:C5" style="display:block;margin: 0 auto;"></iframe>

|

||||

</div>

|

||||

|

||||

In the case that I have small, but interesting data, it would be nice if I could have a GUI for manipulating/entering that data, and could quickly pull it into a program that I'm writing without having to go through lots of hoops. **If I want a good GUI for manipulating tabular data, I should use a spreadsheet!** As it happens, not only can I use Google Sheets for this, but Sheets will let me publish my data to the web for embedding, and Sheets also makes it easy for me to pull the CSV directly. But, I don't want a programmer to know that there's a CSV file waiting for them... I just want them to be able to import the data.

|

||||

|

||||

Something that might look like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import tbl

|

||||

|

||||

pets_url = "https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vSK2rd47ogfI2CpQi2L6HDo9AOEhnhqBN4zR4kLPUO28vBzmlc8XQWrvTfBYCU0ePf478yxcNKdOy5m/pub?gid=0&single=true&output=csv"

|

||||

pets_tbl = tbl_from_sheet(pets_url)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

To test this out, I'll drop some code in `lobsters.py` and `tbl.py`.

|

||||

|

||||

<script src="https://gist.github.com/jadudm/c1e4f42ff3b1abb58f1875e13a646cf1.js"></script>

|

||||

|

||||

When I run

|

||||

|

||||

`python lobsters.py`

|

||||

|

||||

I get the following:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(venv) jadudm@lego:~/git/pytbl$ python lobsters.py

|

||||

['Name', 'Weight', 'Color']

|

||||

['Bart', '0.75', 'Muddy']

|

||||

['Flick', '1', 'Muddy']

|

||||

['Bubbles', '1.2', 'Blue']

|

||||

['Crabby', '0.5', 'Muddy']

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Now, this doesn't get us all the way, but it takes the first step: I've created a data table in Google Sheets, and I can pull it in via the Requests library as a CSV document that is parseable and iterable. So far, so good.

|

||||

|

||||

## Abstractions

|

||||

|

||||

The next step is to design the abstraction for a `tbl`.

|

||||

|

||||

So that no one post gets too long, this will be the subject of tomorrow's explorations. The goal here will be to avoid creating an [abstraction that is overly leaky](https://www.joelonsoftware.com/2002/11/11/the-law-of-leaky-abstractions/), to use Joel Spolsky's terminology. I'm going to want a way to work with this data that:

|

||||

|

||||

* Can store the data locally or remotely

|

||||

* Can work with centralized and decentralized data

|

||||

* Can leverage multiple concrete representations, invisibly

|

||||

* Can operate on the data closer conceptually rather than syntactically

|

||||

* Can support programmers at multiple levels of experience and expertise

|

||||

|

||||

These are going to be a complex set of requirements, and I'll miss the first time. (This is actually the *second time* I've explored this idea; I've already done a deep dive in the programming language Racket, so in truth, I've got some ideas in my back pocket.)

|

||||

|

||||

For the exercise that this is, I'll probably do the following:

|

||||

|

||||

* Explore SQLite for local and CockroachDB for remote/distributed data

|

||||

* Use an ORM (SQLalchemy, Peewee, or similar) to manage those relationships

|

||||

* Use R, Python (pandas), Pyret, and other data languages/frameworks as inspiration

|

||||

* Choose some authentic use-cases to drive the development (e.g. perhaps interface into some of my own research data to drive both the research and the development of `tbl` forward)

|

||||

|

||||

## Get the code!

|

||||

|

||||

It's early days, but you can get the code. This work will be open (as all of my work is, whenever possible), at Github. I'll call the project [pytbl](https://github.com/jadudm/pytbl).

|

||||

70

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/tbl-structure.md

Normal file

70

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/tbl-structure.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,70 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

layout: post

|

||||

title: "tbl: structuring the project"

|

||||

author: mjadud

|

||||

commit: https://github.com/jadudm/pytbl/tree/4433e25769f8ee70da0de363d6589f3c77a96a53

|

||||

tags:

|

||||

- cc-sa

|

||||

- tbl

|

||||

- blog

|

||||

- "2020"

|

||||

- 2020-03

|

||||

date: 2020-03-09

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

It helps, early, to structure a project well.

|

||||

|

||||

Having written a version of `tbl` in another language once before, and now revisiting the design and implementation in Python, I know I should think about how the project is structured from the start.

|

||||

|

||||

I find [The Hitchhiker's Guide to Python](https://docs.python-guide.org/writing/structure/) to be a wholly remarkable book, like it's namesake (*The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy*). As a result, I'll restructure the code around their recommended format for a Python module at this point. `tbl` will become a module that I want to `pip install`, so it makes sense to clean it up now.

|

||||

|

||||

## the layout

|

||||

|

||||

First, I'm going to move some things around. The project directory looks like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 9 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 8 20:10 .

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 7 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 8 20:07 ..

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 2 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 8 20:08 docs

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 8 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 9 08:47 .git

|

||||

-rw-r--r-- 1 jadudm jadudm 25 Mar 8 15:03 .gitignore

|

||||

-rw-r--r-- 1 jadudm jadudm 1093 Mar 8 14:42 LICENSE

|

||||

-rw-r--r-- 1 jadudm jadudm 239 Mar 8 20:42 lobsters.py

|

||||

-rw-r--r-- 1 jadudm jadudm 79 Mar 8 20:11 Makefile

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 2 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 8 15:01 __pycache__

|

||||

-rw-r--r-- 1 jadudm jadudm 1762 Mar 9 08:47 README.md

|

||||

-rw-r--r-- 1 jadudm jadudm 15 Mar 8 14:45 requirements.txt

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 3 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 9 08:07 tbl

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 2 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 8 20:08 tests

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 6 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 8 13:53 venv

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 3 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 9 08:12 .vscode

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Because I want this to become a library that I can `pip install`, I've taken a few necessary steps in that direction. First, I've created a subdirectory called `tbl`, and in that directory, I moved the file previously called `main.py` and called it `__init__.py`. The secret here is that, in Python, any directory containing a file called `__init.py` is considered a *module*. Modules are the fundamental unit of organization for libraries of code, so this is a clear and necessary step.

|

||||

|

||||

Running `ls -al tbl`:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(venv) jadudm@lego:~/git/pytbl$ ls -al tbl/

|

||||

total 20

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 3 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 9 08:07 .

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 9 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 8 20:10 ..

|

||||

-rw-r--r-- 1 jadudm jadudm 2077 Mar 9 08:19 __init__.py

|

||||

drwxr-xr-x 2 jadudm jadudm 4096 Mar 9 08:14 __pycache__

|

||||

-rw-r--r-- 1 jadudm jadudm 406 Mar 9 08:14 util.py

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

I also, in the last commit, created a small utility library. I'll blog about that later.

|

||||

|

||||

At the top level, there are directories for `tests` and `docs`, which I'll begin filling in soon.

|

||||

|

||||

The `.gitignore` is an important file; it says which files and directories I never want to put under version control. For example, my [venv](http://bit.ly/2v6zyON) is something I never want to see in the repository... it's a local working environment for my Python interpreter, so that when I install libraries to support the use of `tbl`, I don't install them globally... instead, they get installed in the `venv` directory. (This, too, is probably a good subject for another post... or, at least, a few more links.)

|

||||

|

||||

The `requirements.txt` says which libraries are needed to support `tbl`. Right now, I have the [hydra](https://github.com/facebookresearch/hydra) library from Facebook (I think I'm going to need it later) and the [requests](https://requests.readthedocs.io/en/master/) library, which makes working with content over the 'net a lot easier.

|

||||

|

||||

It turns out (for those following along) *that the structure of code is often as important, if not moreso, than the code itself*. If I don't place files in the right places, with the right names, then my code is not, and cannot, become a Python library. Similarly, if I want to write an application in Java for Android... some files have to be named specific ways, and be placed in particular places in order for them to be assembed into an app. This is a critical, but sometimes invisible, part of writing code that is too often glossed over when students are getting started programming.

|

||||

|

||||

## structure, complete

|

||||

|

||||

This is a first step in shifting the structure of the project around. There will be more, but for now it brings `tbl` one step closer to being installable as a Python package via `pip`.

|

||||

|

||||

266

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/tbl-testing.md

Normal file

266

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/tbl-testing.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,266 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

layout: post

|

||||

title: "tbl: testing round one"

|

||||

author: mjadud

|

||||

commit: https://github.com/jadudm/pytbl/tree/d6f45ba0c273e847243b9fd5348de5dc949bc8f4

|

||||

tags:

|

||||

- cc-sa

|

||||

- tbl

|

||||

- blog

|

||||

- "2020"

|

||||

- 2020-03

|

||||

publishDate: 2020-03-09

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

In the previous post, I rearranged the structure of the code to align it more closely with what we might expect for a Python package that can be installed via `pip`. It is never too early to begin arranging the structure of a project appropriately, and it is never too early to begin **testing**.

|

||||

|

||||

I have a clear idea of what I expect this project to be, because I've written it before, and written tests, documentation, and a draft paper on it. However, coming soon, I'll need to get those ideas expressed here in something resembling a coherent design. For now, though, I'll continue exploring a bit. But, I'll do it properly.

|

||||

|

||||

My "driver" code right now looks like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import tbl

|

||||

|

||||

pets_url = "https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vSK2rd47ogfI2CpQi2L6HDo9AOEhnhqBN4zR4kLPUO28vBzmlc8XQWrvTfBYCU0ePf478yxcNKdOy5m/pub?gid=0&single=true&output=csv"

|

||||

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = pets_url)

|

||||

a_tbl.show_columns()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

And, when executed, it outputs this:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

Name : None

|

||||

Weight : None

|

||||

Color : None

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

That's fine, because those are the contents of the header row of my spreadsheet. But, saying "it looks right" is no way to test software. Although I haven't articulated a complete design, one thing I know my library will need to be able to do is read a CSV file from a URL and convert it into a `tbl` (a structure that is yet to be fully described).

|

||||

|

||||

So, for my next trick, I'll put some light testing in place. Even though the structures might change, and this might require me to re-write some tests, there are two important things to committing to testing early: first, I can continue exploring with confidence that the code I've written so far is working the way I expect. Second, even if I change the structures over which I'm writing the tests, it should remain true that the tests themselves are "good." Or, put another way, I may have to rewrite the tests, but the tests will be a framework that will remain constant regardless of how the structures change. This will again provide confidence in the library in the face of refactoring, and give me velocity both in terms of development and the development of future tests.

|

||||

|

||||

(Some googling suggests that [there may be more than one way to do it](https://blog.ionelmc.ro/2014/05/25/python-packaging/#the-structure), and that I may have some additional refactoring to do. But, I'll proceed with documentation from [pytest](https://pytest.readthedocs.io/en/2.7.3/index.html) for now, knowing that a first step that is reasonable is better than no step at all.)

|

||||

|

||||

## my friend pytest

|

||||

|

||||

There are many testing frameworks in many languages. I'm going to leverage pytest here because it is lightweight to leverage, and I'll take speed over complexity early in any programming endeavor. And, in truth, I may never need anything more complex than pytest, because it really is quite capable.

|

||||

|

||||

### first problem: not importable

|

||||

|

||||

Uh-oh.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(venv) jadudm@lego:~/git/pytbl$ pip install -e .

|

||||

Directory '.' is not installable. File 'setup.py' not found.

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It looks like I need a `setup.py`. My initial setup looks like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

from setuptools import setup

|

||||

|

||||

setup(name='tbl',

|

||||

version='0.1',

|

||||

description='A tabular way to think about data.',

|

||||

url='http://github.com/jadudm/pytbl',

|

||||

author='Matt Jadud',

|

||||

author_email='matt@jadud.com',

|

||||

license='MIT',

|

||||

packages=['tbl'],

|

||||

zip_safe=False)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

And, now:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(venv) jadudm@lego:~/git/pytbl$ pip install -e .

|

||||

Obtaining file:///home/jadudm/git/pytbl

|

||||

Installing collected packages: tbl

|

||||

Running setup.py develop for tbl

|

||||

Successfully installed tbl

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

That 'pip install' command creates a symlink to my package directory in the venv. This way, I can keep developing the code and running tests, and I will always be testing against the "live" code.

|

||||

|

||||

I can now run `python3 -m pytest`, and get:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(venv) jadudm@lego:~/git/pytbl$ python3 -m pytest

|

||||

======================================= test session starts ========================================

|

||||

platform linux -- Python 3.6.9, pytest-5.3.5, py-1.8.1, pluggy-0.13.1

|

||||

rootdir: /home/jadudm/git/pytbl

|

||||

collected 0 items

|

||||

|

||||

====================================== no tests ran in 1.03s =======================================

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This is good.

|

||||

|

||||

## testing one function

|

||||

|

||||

At this point, I want to test the import of the CSV file. There's a lot of tests I can run at this point, because (really) my first function is almost too complex.

|

||||

|

||||

What if the programmer using `tbl`...

|

||||

* gives me a bad URL?

|

||||

* says there is a header, but there isn't?

|

||||

* says there isn't a header, but there is?

|

||||

* gives me a spreadsheet with a header and no data?

|

||||

* gives me a URL to more data than I can hold in memory?

|

||||

* gives me a URL to more data than I can store on disk?

|

||||

* gives me a URL to something that is not a CSV/spreadsheet?

|

||||

* gives me a spreadsheet with data, and a header, and says it has a header?

|

||||

|

||||

The last one is actually the easy/ideal case. The others are failure cases, some of which might be difficult to catch early. But, anywhere you give a programmer the ability to pull data in---especially over the network---you have to begin thinking in a *really* paranoid way. And, when dealing with novice programmers, they might be taking random stabs at things, or (more likely) really trying hard to figure things out, but this will still be in the space of "desperate guessing" in some cases.

|

||||

|

||||

So, time to write some tests.

|

||||

|

||||

### a bad URL

|

||||

|

||||

What is a "bad" URL? In this case, we'll call it a URL that does not point to a CSV file, or (worse) is simply not a URL. This could look like the following:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = True)

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = 1)

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "lobster")

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = [True])

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = [1])

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = ["lobster"])

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = ["https://lobster.org/northaven.csv"])

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "http")

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https")

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://lobster")

|

||||

# Technically, this is a good URL, but we have no idea if

|

||||

# it serves up a CSV file.

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://lobster.org/")

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://lobster.org/northhaven")

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://lobster.org/northhaven.txt")

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This has begun to suggest what we're going to consider a "good" URL. This may not be obvious, but I'm going to bet money that *validating URLs is hard*. There's whole specs on how to format a URL/URI, so... why would I want to try and write this myself? A bit of googling confirms that Python has what I want: a [validation](http://bit.ly/2vVxzx4) package for URLs (and other stuff). I found this from a Stack Overflow thread, which (had I followed the first recommendation), I would have ended up implementing my own. *Not a good idea*.

|

||||

|

||||

I'm going to have to do the checking inside of the call to the `tbl` constructor, but I'll farm it out to a helper function. I've created a module called `validation.py` that will contain all of my validation code, so that the class doesn't get too heavy. (Is this good OOP? Probably not.)

|

||||

|

||||

My first validation function looks like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import validators as val

|

||||

from collections import namedtuple as NT

|

||||

import re

|

||||

|

||||

OK = NT("OK", [])

|

||||

KO = NT("KO", ["code", "message"])

|

||||

|

||||

# Error Codes

|

||||

BAD_URL = 0

|

||||

DOES_NOT_END_IN_CSV = 1

|

||||

URL_NOT_A_STRING = 2

|

||||

|

||||

def _check_from_sheet(url, has_header):

|

||||

# These will "fail fast."

|

||||

# Make sure it is a string.

|

||||

if not isinstance(url, str):

|

||||

return KO(URL_NOT_A_STRING, "The URL you passed does not look like a string: {}".format(url))

|

||||

if not val.url(url):

|

||||

return KO(BAD_URL, "The URL '{}' appears to be invalid.".format(url))

|

||||

# Should the URL end in CSV? Am I guaranteed that a Google Sheets

|

||||

# CSV URL will end this way? This might get tricky.

|

||||

# If it is a sheets URL, and the letters "csv" appear in the URL, it will be OK.

|

||||

if (re.search("docs.google.com", url)

|

||||

and re.search("spreadsheets", url)

|

||||

and re.search("csv", url)):

|

||||

return OK()

|

||||

# If it isn't a sheets URL, then perhaps it is a valid URL that

|

||||

# just points to a CSV. Therefore, it should end in '.csv'.

|

||||

if not (re.search(".csv$", url) or re.search(".CSV$", url)):

|

||||

return KO(DOES_NOT_END_IN_CSV, "The file you linked to does not end in '.csv'.")

|

||||

return OK()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

I've created two unique types -- OK and KO -- and started defining some error codes. I don't know how I'll use them yet, but I do like the idea of being able to ask if something is `validation.OK()`. Now, I need to see if I can write test code for all of the above examples, and get back responses that I expect.

|

||||

|

||||

This has turned into the following test file:

|

||||

|

||||

```python

|

||||

import tbl

|

||||

from tbl import validation as V

|

||||

|

||||

pets_url = "https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vSK2rd47ogfI2CpQi2L6HDo9AOEhnhqBN4zR4kLPUO28vBzmlc8XQWrvTfBYCU0ePf478yxcNKdOy5m/pub?gid=0&single=true&output=csv"

|

||||

|

||||

def test_bool_url():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = True)

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_int_url():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = 1)

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_url_str_not_url():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "lobster")

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_url_list_bool():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = [True])

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_url_list_int():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = [1])

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_url_list_str():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = ["lobster"])

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_list_good_url():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = ["https://lobster.org/northaven.csv"])

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_protocol():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "http")

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_protocol_s():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https")

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_partial_url():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://lobster")

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

# Technically, this is a good URL, but we have no idea if

|

||||

# it serves up a CSV file.

|

||||

def test_good_url_not_csv():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://lobster.org/")

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_good_url_not_csv2():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://lobster.org/northhaven")

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_good_url_txt():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://lobster.org/northhaven.txt")

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_goog_url_incomplete():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vSK2rd47ogfI2CpQi2L6HDo9AOEhnhqBN4zR4kLPUO28vBzmlc8XQWrvTfBYCU0ePf478yxcNKdOy5m/pub?gid=0&single=true")

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.KO

|

||||

|

||||

def test_complete_goog_url():

|

||||

a_tbl = tbl.tbl(url = "https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/e/2PACX-1vSK2rd47ogfI2CpQi2L6HDo9AOEhnhqBN4zR4kLPUO28vBzmlc8XQWrvTfBYCU0ePf478yxcNKdOy5m/pub?gid=0&single=true&output=csv")

|

||||

assert type(a_tbl.fields.status) is V.OK

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It feels repetitious. In fact, I now realize that I could create some tables/lists of input data, and do all of this testing in a loop. However, I'll leave this for the moment: I now have good tests over the possible inputs a user might throw my way, and that makes me happy.

|

||||

|

||||

### error codes, or exceptions?

|

||||

|

||||

What should this library do if a user provides a bad URL? Should a_tbl be an object that is in a bad state, but the object knows it, and therefore won't do bad things? Or, should the object throw exceptions, causing the user's code to crash out?

|

||||

|

||||

This question has answers that are less obvious than I would like. There are different schools of thought on language/class design around the topic of exceptions. Python likes exceptions, golang prefers error codes. This will require some thought and a bit more reading, as I prefer the latter, but wonder if it is more important to be Pythonic.

|

||||

|

||||

And, regardless of whether it is "Pythonic," the question really is "what would be most usable to a novice programmer working with data?"

|

||||

|

||||

## still not done testing...

|

||||

|

||||

And, if you're still reading, you'll realize that I'm not done testing. That is, I had imagined more ways the user might try and abuse my library than I actually tested for. So far, I've only handled the "bad URL" condition. What if the CSV they hand me is malformed? That's another whole round of validation that has to come after I check if the CSV URL is even valid. Then, I have to check if I can fetch the URL, and if it is a reasonable size, and ...

|

||||

|

||||

For tomorrow. For tonight, I've made progress.

|

||||

35

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/tbl.md

Normal file

35

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/03/tbl.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,35 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

layout: post

|

||||

title: "tbl: thinking about data"

|

||||

author: mjadud

|

||||

commit: https://github.com/jadudm/pytbl/tree/527b16bdecbf73b874103922cf3038a1f2c1e1c7

|

||||

tags:

|

||||

- cc-sa

|

||||

- tbl

|

||||

- blog

|

||||

- "2020"

|

||||

- "2020-03"

|

||||

date: 2020-03-07

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

For the past six months, I have been working in a space where all of my intellectual output was owned by the company I worked for. As a result, there were projects that simply had to sit. That time has passed, and I have two that I want to revisit: the teaching and learning of data science in the broader context of computing, and my own explorations regarding the principles and practices that tooling can embody when it comes to working with data. I might even sneak some IoT/embedded systems in, but there are only so many hours in the day.

|

||||

|

||||

I'll probably sneak some articles about hardware and firmware design in here as well, because that's part of the data chain, so-to-speak.

|

||||

|

||||

## teaching and learning of data

|

||||

|

||||

Last spring and summer, I was thinking hard about the teaching and learning of <em>data</em>.

|

||||

|

||||

<a href='https://photos.google.com/share/AF1QipM4nF5IbEJk0q4EiMI6V1XxYRkkyKpoLCOqjEEnpjwtkOJL7kb4ahZOEUF65Xq5Ow?key=RlNDSUNSZjUxc1dqQ0lfWjFiT2hsYkI0RURodWpn&source=ctrlq.org'><img src='https://lh3.googleusercontent.com/7_4aQQPN_0_ppLSk-nH8JxGJIX8wjsRk4MAP84SBg--IJ0HXZwXA0BWHawnrHf1JgzHhmfeGYsD31wD_rDTrVWSe0ghN6lnzin9WlNo6TizymBqPjmIIVhtlkQtFvTqOq9ICXMdvQik=w2400' /></a>

|

||||

|

||||

Along with my colleague at Fulbright University Vietnam, <a href="https://fulbright.edu.vn/our-team/sebastian-dziallas/">Sebastian Dziallas</a>, we began laying out a two-course sequence that would introduce students to human-centered principles of collectiong, working with, and questioning data in deep and meaningful ways. Who asks the questions? Who collects the data? How is it collected? What biases do we bring to the analysis? How do we report our findings, and to whom? What hardware and software is needed to support this learning in active and meaningful ways?

|

||||

|

||||

This is one space that I will begin documenting and unpacking here. Sebastian and I spent a year discussing related topics prior, and put in weeks of intense work on this during the summer. It has been unpacked (in part) in notes and documents, but should be unpacked more fully before the memory fades completely.

|

||||

|

||||

## embodied ideas in tooling

|

||||

|

||||

One red thread to my time at Bates was thinking hard about how you introduce programming and the analysis of data to students from across the full breadth of the liberal arts. Computation has a place in every discipline, but <em>how</em> and <em>why</em> it is employed varies greatly. Artists might work with real-time data as part of performance, while social scientists generate their data through survey and interview, while natural scientists might use experiment or simulation to develop the data that informs their analysis. The context to each of these matters, the computational tools are not strictly the same, and the metalearning is drastically different in each case. What, then, become the driving <em>principles</em> that might unify these kinds of inquiry, and how can those principles be exemplified in the teaching and tooling that we bring to our students?

|

||||

|

||||

To explore this, I began work on <code>tbl</code>, a library of code in Racket that explores these concepts.

|

||||

|

||||

Now that I am once again free to author open code and write about my ideas without them explicitly being owned by others, I will be revisiting this work here over the coming weeks.

|

||||

7

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/_index.md

Normal file

7

jadudcom/content/blog/2020/_index.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

title: 2020

|

||||

weight: 80

|

||||

description: All posts in 2020

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

{{< listofposts "2020" >}}

|

||||

40

jadudcom/content/blog/2025/09/2025-09-16-wbc.md

Normal file

40

jadudcom/content/blog/2025/09/2025-09-16-wbc.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,40 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

layout: post

|

||||

title: "wbc: generating xlsx"

|

||||

author: jadudm

|

||||

draft: true

|

||||

# commit: https://github.com/jadudm/pytbl/tree/527b16bdecbf73b874103922cf3038a1f2c1e1c7

|

||||

tags:

|

||||

- cc-sa

|

||||

- wbc

|

||||

- blog

|

||||

- "2025"

|

||||

- 2025-09

|

||||

date: 2025-09-16

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

Generating Excel workbooks in code is hard. By this, I mean that writing code that outputs an XLSX document involves a lot of details (contents, formatting, data validations), and you have to learn a lot about XLSX in order to do it right.

|

||||

|

||||

**But Matt: who would ever want to generate Excel documents from code?**

|

||||

|

||||

It turns out, most everyone who works with data. Also, *every government everywhere*. Spreadsheets are the lifeblood of governments around the world. Also, financial institutions. And researchers. And... and...

|

||||

|

||||

## a workbook "compiler"

|

||||

|

||||

For a number of months (years?), I've been thinking about writing a workbook "compiler." In technical terms, a compiler transforms one language or representation of content to another while preserving the intention of the programmer. In this case, I want a way to express a workbook in one language (say, a textual representation like JSON) and I want to transform it to another representation (an XLSX document, or spreadsheet).

|

||||

|

||||

For example, I'd like to be able to say write something like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```json

|

||||

{

|

||||

"workbook": "my first spreadsheet",

|

||||

"sheets": [

|

||||

{

|

||||

"name": "empty sheet"

|

||||

}

|

||||

]

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

and run a program that consumes that textual file, producing as output the XLSX document.

|

||||

|

||||

8

jadudcom/content/blog/2025/09/_index.md

Normal file

8

jadudcom/content/blog/2025/09/_index.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,8 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

title: Sept 2025

|

||||

# type: blog

|

||||

weight: 10

|

||||

description: All posts in September 2025

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

{{< listofposts "2025-09" >}}

|

||||

8

jadudcom/content/blog/2025/_index.md

Normal file

8

jadudcom/content/blog/2025/_index.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,8 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

title: "2025"

|

||||

# type: blog

|

||||

weight: 75 # 2025 - 2000

|

||||

description: All posts in 2025

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

{{< listofposts "2025" >}}

|

||||

7

jadudcom/content/blog/_index.md

Normal file

7

jadudcom/content/blog/_index.md

Normal file

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

|

||||

---

|

||||

title: das blog

|

||||

description: All posts in th blog

|

||||

weight: 50

|

||||

---

|

||||

|

||||

{{< listofposts "blog" >}}

|

||||

Reference in New Issue

Block a user